Abstract

Aim

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in hospital with orthopaedic surgery already an established risk factor. This study aims to establish the length of time that a patient is at risk of sustaining a VTE post orthopaedic surgery.

Method

A retrospective case series of all patients who underwent orthopaedic surgery between 2010 and 2014 whom re-presented with a VTE within one year of their initial operation. Demographic, operative and clinical information was obtained in order to identify potential risk factors.

Results

53 patients were identified as having a VTE within one year of discharge. The majority (63.4%) underwent lower limb arthroplasty. 29% of the cohort had either a family or personal history of VTE, 79% had ischaemic heart disease (IHD), hypertension or both. The average body mass index (BMI) of the cohort was 31.4; above the UK national average. 56.6% of the cohort developed a pulmonary embolism (PE) and 49% developed a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Co-occurring DVT and PE was diagnosed in 5.6% of patients. The average length of time for readmission for patients to re-present at hospital with a PE was 122 days (range 4-361) and 107 days (range 7 – 360) with a DVT.

Conclusion

This study confirms the existence of pre-established risk factors for developing VTE including obesity, personal and family history of DVT, cardiovascular disease and lower limb arthroplasty. These risk factors are recognised despite patients receiving post-operative thromboprophylaxis.

The findings of this study extend the current research by suggesting that patients presenting with known risk factors of developing VTE may be at risk for longer than the current guidelines cover for the administration of thromboprophylaxis. We propose further studies are needed to identify any potential requirements for more extensive VTE prophylaxis in this population.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Roman Kireev, PhD, Senior Researcher

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2017 Nikhil Nanavati,et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a collective term referring to the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). VTE is a commonly encountered diagnosis that can result in serious morbidity and a reported mortality of 10.6% within 30 days and 23% at one year1. VTE can present in numerous different ways. Classically a patient with DVT will present with pain and swelling of the leg. A patient with PE is likely to present with symptoms such as chest pain, tachycardia, dyspnoea and haemoptysis2.

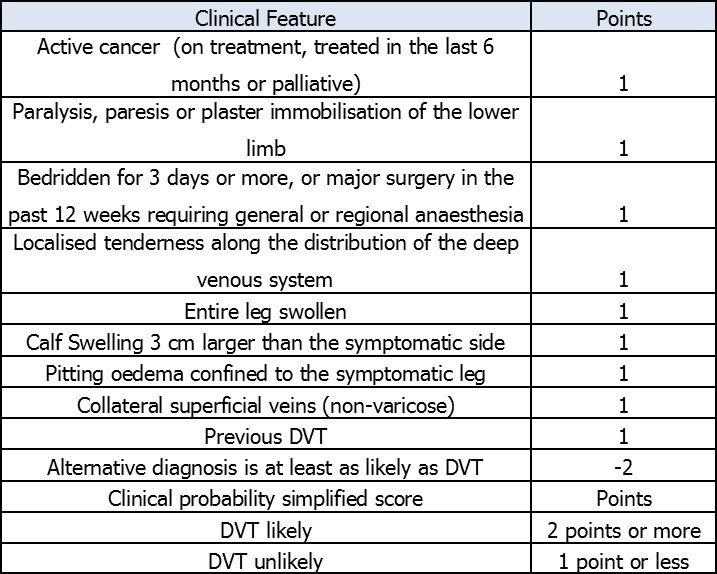

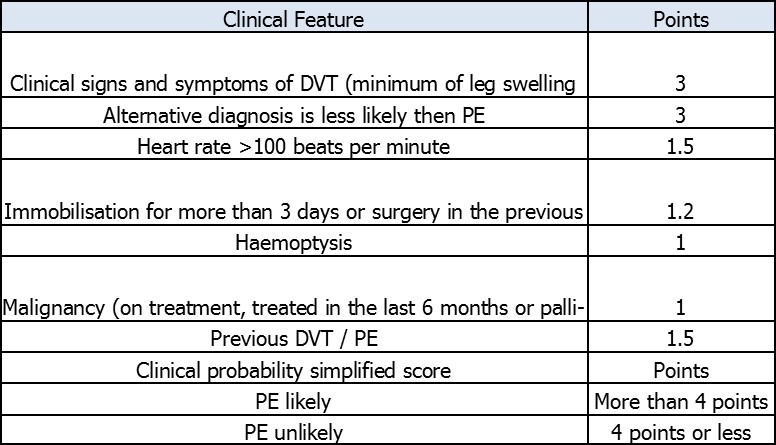

In 2005, the House of Commons Health Committee reported that 25,000 people in the UK die from preventable VTE each year3 and NICE guidelines were introduced to facilitate an early reproducible process, which would allow prompt diagnosis and management of these patients.4 The guidance is predominantly based around the 2 level Wells score for both DVT5 (Figure 1) and PE6 (Figure 2) with the outcome of the score determining which subsequent investigation is performed. Even with the use of scoring systems such as this, it is down to the clinician to have a high index of suspicion for VTE where appropriate.

Figure 1.Two level DVT Wells score

Figure 2.Two level PE Wells score

Previously established significant risk factors for VTE include trauma, cancer, advanced age, obesity, family/personal history, cardiovascular disease, race15 and surgery7. Within surgery, orthopaedic procedures carry the highest risk, (1 in 45 after hip or knee replacement) second only to oncology8. Prior to discharge from a surgical unit, the index of suspicion for VTE is high. It is known that certain orthopaedic operations such as arthroplasty, pelvic fracture fixation and lower limb casts following foot & ankle surgery carry an increased risk of developing a VTE; therefore these patients commonly receive prolonged post-operative VTE prophylaxis for 28 days following total knee arthroplasty and 35 following total hip arthroplasty; according to NICE guidance CG92 or local trust policy. Recent evidence has also shown that increased surgical time increases the likelihood of a VTE post-operatively9. This heightens the risk of VTE in some orthopaedic procedures due to the nature of surgery and length of operative time required. Despite following guidance it is well evidenced that some patients continue to present with VTE following the cessation of prophylaxis10, 11

Method

The objectives of this study were to determine: what risk factors for VTE were present in patients who underwent orthopaedic surgery in specialised trauma unit and to establish the length of time that a patient is at risk of sustaining a VTE post orthopaedic surgery including the interval between their initial operative procedure and the subsequent presentation of VTE.

Study Design

A retrospective case series of patients who underwent an orthopaedic procedure at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust – (Northern General Hospital) and re-presented to the trust with a subsequent VTE within one year of their initial operation. The study period was from 1/1/2010 to 31/12/2014. In order to be included patients must:

Have undergone an orthopaedic opertation recorded on ORMIS within the study period

Have undergone any imaging with coded as positive for VTE on PACS (electronic imaging software)

Any patients whom did not meet the inclusion criteria above were excluded from the study.

All eligible patients were identified and matched using an electronic patient database. Paper notes were requested for each patient who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and a team of two orthopaedic trainees then examined the notes using a 24-question proforma.

Proforma

The proforma was a 3 page, A4 document that included:

Patient demographics; age, height, weight, BMI and gender.

Operative and anaesthetic information: Name of procedure, length of surgery, site of surgery and type of anaesthesia

Post-operative information: Intensive care transfer, time to mobilise, physiotherapy, thromboprophylaxis used both immediate post operatively and extended VTE if indicated

Past Medical history: Significant co-morbidities, Family/Personal history of VTE

Biochemistry: Creatinine, Urea, INR

VTE information; PE, DVT, site of DVT, timing of DVT from operation

Analysis

The data was converted from the proforma into a computerised spreadsheet and analysed to determine any trends within the study population. The study population was then split into sub-groups for further statistical analysis

Sheffield teaching hospitals VTE guidance

All patients included in this study received care based on local inpatient guidelines for extended VTE prophylaxis. All patients are risk assessed on admission to hospital using local clerking document to establish risk factors(Table 1). Subcutaneous Dalteparin is the low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) recommended for use in inpatients at Sheffield teaching hospitals for the prevention of VTE. The recommended dosing of Dalteparin is summarised in Table 2. According to local guidelines, a proportion of orthopaedic patients will be offered extended thromboprophylaxis post discharge from hospital as shown in Table 3.

Table 1. Risk factors for (VTE):| Patient-related risks | Admission-related risks |

| Active cancer or cancer treatment | Significantly reduced mobility for 3 day or more (relative to normal state) |

| Age greater than 60 years | Hip or knee replacement |

| Dehydration | Hip fracture |

| Known thrombophilia’s | Total anaesthetic plus surgical time over 90 minutes |

| One or more significant medical | Surgery involving pelvis or lower limb with a total anaesthetic plus surgical time over 60 minutes |

| co-morbidities e.g. heart disease, metabolic, endocrine or respiratory pathologies; acute infectious diseases; inflammatory conditions | |

| Obesity (body mass index over 30kg/m2) | Acute surgical admission with inflammatory or intra-abdominal condition |

| Personal history or first-degree relative with a history of VTE | Critical care admission |

| Use of hormone replacement therapy | Surgery with significant reduction in mobility |

| Use of the combined oral contraceptive | |

| Varicose veins with phlebitis | |

| Pregnancy or puerperium (up to 6 weeks after delivery) | |

| Risk factors for bleeding include the following | |

| Patient-related risks | Admission-related risks |

| Active bleeding | Neurosurgery, spinal surgery or eye surgery |

| Acquired bleeding disorders (such as acute liver failure) | Other surgical procedure with a high bleeding risk |

| Concurrent use of anticoagulants known to | Lumbar puncture/ epidural/ spinal anaesthesia expected within the next 12 hours |

| increase the risk of bleeding | |

| Acute stroke | Lumbar puncture/ epidural/ spinal anaesthesia within the previous 4 hours |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelets less than 75 x 109/L) | |

| Uncontrolled hypertension (greater than or equal to 230mmHg systolic or 120 mmHg diastolic) | |

| Untreated inherited bleeding disorders (such as haemophilia and von Willebrand’s disease) | |

| Patient’s weight to nearest | eGFR greater than or equal to | eGFR less than |

| kilogram | 20 mL/min/1.73m2 | 20 mL/min/1.73m2 |

| Less than 45kg | 2,500 units once daily | 2500 units once daily |

| 45-99kg | 5,000 units once daily | |

| 100-149kg | 7,500 units once daily | |

| 150kg and greater | 5,000 units twice a day |

| Operation | Thromboprophylaxis | Dose | Duration |

| Elective hip arthroplasty | Rivaroxaban | 10mg once daily | 30 days |

| Elective knee arthroplasty | Rivaroxaban | 10mg once daily | 10 days |

| Pelvic surgery | Warfarin | INR target 2-3 | 3 months |

| Patients with lower limb casts | Rivaroxaban | 10mg once daily | Until removal of cast |

Results

Demographics

53 patients from the hospital database were identified who had sustained a VTE confirmed on imaging within 12 months of having an orthopaedic operation. Of whom 24 were male and 29 were female, with a sex ratio of 1:1.2 (M:F).

The mean age of patients was 67.3 years (range 31-89 years). The mean BMI was 32.2 for Females (range 20-48) and 30.6 for Males (range 20-42) with an overall average of 31.4; higher than the UK average of 24.7812

Past Medical History

29% of patients included in the study had either a family or personal history of VTE. Co-morbidity data (Table 4) showed that 85.6% of the cohort had one or more existing medical conditions. Only 14% had no other diagnosed conditions. Of those with co-morbidities, 79% had ischaemic heart disease (IHD), hypertension or both.

Table 4. Co-morbidity data of patient cohort| Co-morbidity | Number of patients |

| Hypertension | 20 |

| Ischaemic Heart disease | 13 |

| No co-morbidity | 6 |

| Parkinson’s | 3 |

| Arrhythmia | 2 |

| T2DM | 3 |

| Cancer | 3 |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 1 |

Operative and Anaesthetic Information

64% of patients underwent either primary or revision arthroplasty (Table 5). The mean surgical time for the cohort was 101 minutes (20-260 minutes). Surgical time data was similar for the arthroplasty patients with a mean time of 105 minutes (76-240 minutes). Anaesthetic data showed that 69% received a spinal anaesthetic, 39% of patients had a general anaesthetic and 2% had local anaesthetic.

Table 5. Number of patients receiving arthroplasty| Type of arthroplasty performed | Number performed |

| Primary THR | 15 |

| Primary TKR | 13 |

| Revision TKR | 3 |

| Revision THR | 2 |

| Primary total ankle replacement | 1 |

VTE Information

Thromboprophylaxis was given in accordance with local trust policy and based on patient specific risk assessments. All patients’ received the recommended VTE prophylaxis by mechanical intervention (TED stockings), pharmacological intervention (LMWH) or both. 30 of the 53 patients had a PE and 26 had a DVT. 3 patients had both DVT and PE at the time of presentation.

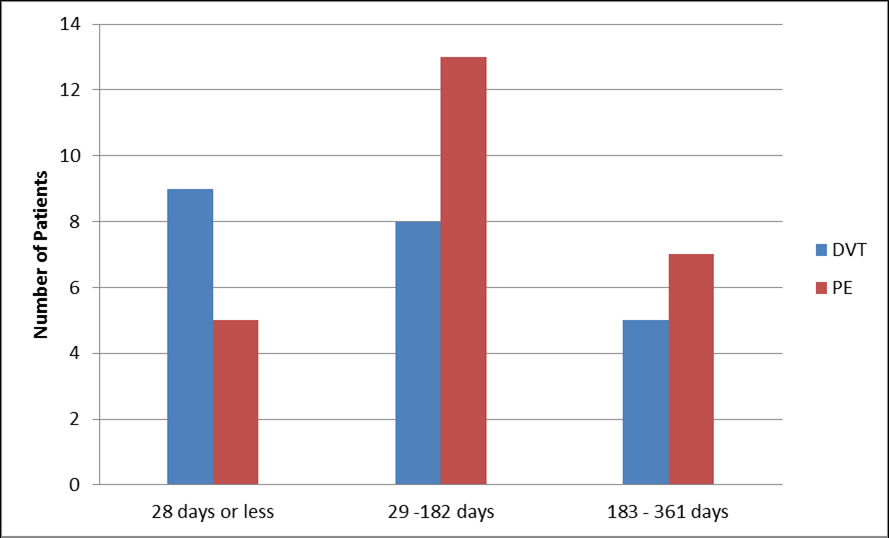

In patients who had developed a PE, the average time between the initial operation and readmission was 122 days (range 4-361) including 8 patients who presented more than 200 days post operatively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.Average time lapsed from operation to redmission with VTE.

In patients who had developed a DVT, the average time between the operation and the admission with DVT was 107 days (range 7 – 360) post op.

In the patients who had operations on the hip and lower limbs, 76% had a DVT on the ipsilateral side and presented at an average of 77 days. Patients with a DVT on the opposite side typically presented later at an average of 147 days.

Discussion

This retrospective study investigated patients who re-presented with a VTE following discharge post orthopaedic surgery at Sheffield Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (NGH). The study supports the current literature regarding specific risk factors for developing PE such as obesity, arthroplasty surgery and personal or family history of VTE13. Over 85% of the study sample had one or more co-morbidities. The most predominant risk factors identified in this cohort were hypertension and IHD, or commonly both.

It could be hypothesised that due to their impaired cardiovascular function, these patients are less mobile and thus at a higher risk of developing a VTE. It should also be considered that vessel wall damage due to hypertension is more likely to lead to thrombus formation and thus a thromboembolic event. This could suggest the need for extended VTE prophylaxis in an already at risk population, with recognised risk factors, compared to patients without risk factors.

This study supports previously established data that VTE can occur despite prophylaxis14 with one third of re-presentations with were receiving on-going pharmacological prophylaxis at the time of VTE diagnosis.

Up to 6 months post-surgery, the data showed that 76% of DVTs presented on the ipsilateral side following lower limb or hip operations, however following the initial 6 month period, the trend reversed and the contralateral leg was more frequently affected.

It seems likely from study, that in the short term, immobility of the affected leg coupled with local inflammatory factors and probable post-operative vascular disruption increases the likelihood of a DVT occurring on the ipsilateral side. As time passes however, it could be suggested that such local factors have less impact and pre-existing and established risk factors influence the likelihood of a patient having equal chance of developing a DVT in both legs respectively.

When using the Wells score a patient gains one point for ‘surgery within 4 weeks’ for PE, or 12 weeks for DVT. Within this current cohort, 46% of DVTs and 79% of patients presenting with PE presented after this window and would not have scored a point. It may be the case that later presenting VTE are unrelated to the initial surgery although we feel this may highlight the need for clinical suspicion in patients with risk factors and an orthopaedic surgical history outside the 4 week timeframe.

This study shows that the majority of patients present with VTE following the cessation of the recommended post-operative pharmacological prophylaxis, according to local guidelines. This could suggest that current guidance for thromboprophylaxis is not extensive enough and that patients should be offered prophylaxis for a longer duration if appropriate when considering additional risks and complications.

Limitations

This study only reviewed patients who re-presented locally. NGH is the regional centre for orthopaedics and patients who were admitted to other hospitals are not included in this study.

No formal imaging took place prior to operating in any of the patients in this study and it may be the case that they had an undiagnosed VTE before their operation.

It may be the case that patients who re-presented did not have a VTE confirmed on imaging due to empirical treatment or operator skill and will have therefore not been included in this study.

A proportion of patients may have developed an asymptomatic VTE and thus not re-presented.

As this is a retrospective study using patient notes, co-morbidities, family history and personal history of VTE may not have been recorded and it is likely that this study underestimates the prevalence of these factors

Conclusions

This study supports that previously evidenced risk factors such as obesity, personal and family history of DVT, cardiovascular disease, long operative time and arthroplasty may increase a patient’s risk of developing a VTE despite the administration of post-operative VTE prophylaxis.

Current guidance on VTE prophylaxis in arthroplasty, pelvic surgery and patients in lower limb casts suggest extended thromboprophylaxis post-operatively. However this study suggests that patients presenting with risk factors, as outlined in this study, may be at an increased risk of developing VTE for a prolonged period of time. This study has several limiting factors including: only including patients from a single trust and a lack of demographic data available for patients undergoing surgery and not representing with a VTE resulting in an inability to conduct a true cohort study.

Community physicians, Emergency Department clinicians and orthopaedic surgeons should approach VTE with a high index of suspicion in any patient following an orthopaedic operation. We feel further research into this area is required to compare risk factors following orthopaedic surgery in patients who either did, or did not, develop a VTE after an extended period.

References

- 1.Tagalakis V, Patenaude V, Kahn S, Suissa S. (2013) Incidence of and Mortality from Venous Thromboembolism in a Real-world Population: The Q-VTE Study Cohort. , The American Journal of Medicine.126(9),pp.832.e13-832.e21

- 2.García-Sanz M, Pena-Álvarez C, López-Landeiro P, Bermo-Domínguez A. (2014) Symptoms, location and prognosis of pulmonary embolism. Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia. 20(4), 194-199.

- 3.House of Commons Health Committee. (2005)The prevention of venous thromboembolism inhospitalised patients. London: The StationeryOffice Limited.(Guideline Ref ID:HOUSEOFCOMMONS2005).

- 4.Nice org uk. (2010) Venous thromboembolism: reducing the risk | introduction | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. [online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg92/chapter/Introduction [Accessed29Apr.2015].

- 5.Wells P, Anderson D, Rodger M, Forgie M. (2003) Evaluation of D-Dimer in the Diagnosis of Suspected Deep-Vein Thrombosis. New England. , Journal of Medicine 349(13), 1227-1235.

- 6.Wells P. (1998) Use of a Clinical Model for Safe Management of Patients with Suspected Pulmonary Embolism. Annals of Internal Medicine. 129(12), 997.

- 7.Gould M K, Garcia D A, Wren S M. (2012) Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.Chest.141(2)(suppl):e227S-e277S.

- 8.Sweetland S, Green J, Liu B, A Berrington de Gonzalez, Canonico M. (2009) Duration and magnitude of the postoperative risk of venous thromboembolism in middle aged women: prospective cohort study.BMJ,339(dec03,1)pp.b4583-b4583.

- 9.Kim J, Khavanin N, Rambachan A, McCarthy R. (2015) Surgical Duration and Risk of Venous Thromboembolism. , JAMA Surgery 150(2), 110.

- 10.Motohashi M, Adachi A, Takigami K, Yasuda K. (2012) Deep Vein Thrombosis in Orthopedic Surgery of the Lower Extremities. Annals of Vascular Diseases. 5(3), 328-333.

- 11.White R H, Romano P S, Zhou H. (2001) A population-based comparison of the 3-month incidence of thromboembolism after major elective/urgent surgeries. Thromb Haemost. 86, 2255.

- 12.Walpole S, Prieto-Merino D, Edwards P. (2012) The weight of nations: an estimation of adult human biomass. BMC Public Health. 12(1), 439.

- 13.Goldhaber S. (2010) Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism. , Journal of the American College of Cardiology 56(1), 1-7.

- 14.Warwick D, Friedman R, Agnelli G, Gil-Garay E. (2007) Insufficient duration of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip or knee replacement when compared with the time course of thromboembolic events:. FINDINGS FROM THE GLOBAL ORTHOPAEDIC REGISTRY.Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-British. Volume89-B(6) 799-807.

Cited by (3)

- 1.Huwae Thomas Erwin Christian Junus, Heifan Ahmad, Sugiarto Muhammad Alwy, 2021, Correlation of Wells Score, Caprine Score, and Padua Score with Risk of Hypercoagulation Condition Based on D-dimer in Intra-articular, Periarticular, and Degenerative Fracture Patients of Inferior Extremity, Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 9(B), 1580, 10.3889/oamjms.2021.7252

- 2.Wang Yiqun, Xu Xiaobin, Zhu Wei, 2024, Anticoagulant therapy in orthopedic surgery – a review on anticoagulant agents, risk factors, monitoring, and current challenges, Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery, 32(1), 10.1177/10225536241233473

- 3.Todd F., Yeomans D., Whitehouse M.R., Matharu G.S., 2021, Does venous thromboembolism prophylaxis affect the risk of venous thromboembolism and adverse events following primary hip and knee replacement? A retrospective cohort study, Journal of Orthopaedics, 25(), 301, 10.1016/j.jor.2021.05.030